Kuusamo became part of the church when the bishop of Turku founded the Kemi Lapland parish in 1673. Its first vicar was Gabriel Tuderus, that “priest of the Lord who was hated by both the settlers and the Sámi”. A large congregation was formed throughout eastern Lapland as far as Inari. When Kuusamo was designated as the centre of the parish in the 1690s, people started to call it the “Kuusamo parish”.

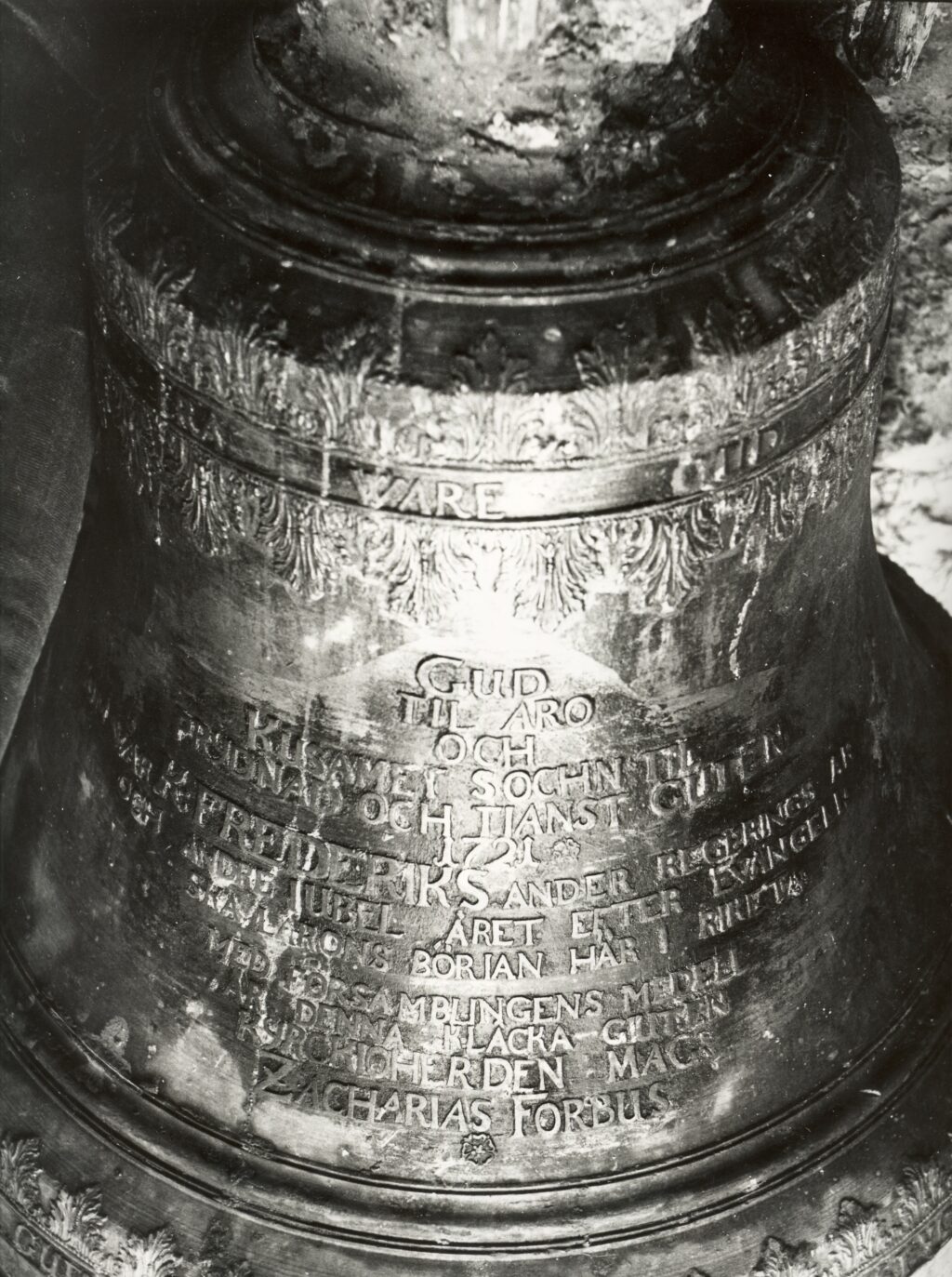

In 1687, a small pulpit was built in Kuusamo. In the following decade, the first real church was completed on the site of the current church, a 17-meter long and wide log cross church. A belfry rose next to it, where the bell donated by King Charles XI was raised. Gradually, the staff of the parish also became established, which together with the vicar came to include a bellringer in charge of the hymns, whose tasks from the 1720s were attempted to include teaching reading and writing skills. The churchwarden acted as trustee of the parishioners, whose main task was to take care of the parish buildings.

Kuusamo’s congregation was very large in the 18th century. In the north, it stretched to the border of Norway, including all eastern Lapland between Kuusamo and Inari. The vicar of Kuusamo used to make a trip that lasted a whole month during the winter, during which he stayed in Inari, Sodankylä and Kuolajärvi on his official duties. However, there were chaplains living permanently in Kemijärvi and Sodankylä, who were in contact with the parishioners of their nearby areas.

As the population increased, the first church became cramped. In its place, a dome-roofed church representing the so-called wooden baroque style was built at the beginning of the 19th century.

The state administration in Kuusamo came to be represented by a lensmann, although the higher state authorities and subjects both considered his powers questionable in the 17th century. Sigfrid Granroth, who was appointed to the post in 1703, got a tax-free estate of a lensmann in Kantoiemi in the village of Poussu to live in and established the power and authority of the lensmann.

In the courts, in addition to disputes and criminal cases, the lensmann resolved the most important issues in terms of Kuusamo’s development, legal appeals for peasants’ new farms and farmland. The newly established farms and the cleared farmland were entered in the administrator’s list of seven village municipalities. The mantal number of each farm indicating the extent of the farmland was recorded in it. This important document confirmed the ownership of the land and based on it the owner of the farm paid his taxes. Farmlands were initially located close to the place of residence, but as arable land decreased, new cultivations had to be done even in long distances, which made it difficult to use them. This problem was solved in the Great Partition in most Finnish parishes. The people of Kuusamo, on the other hand, entered into a so-called local militia agreement with the Swedish government. It gave them an exemption from implementing the Great Partition, in return for which the people of Kuusamo undertook to maintain a small army of soldiers on the Russian border. The agreement had far-reaching consequences, as the Great Partition was delayed for a long time. The Great Partition was only carried out in Kuusamo in the 1960s.

Many people gathered for the trials held in Kantokylä. During them, a market was organized, where sellers and buyers came from the entire northern coast of Norway, Sweden, and Russia. Until the end of the 19th century, Kantokylä was the busiest of Kuusamo’s villages.

When the county of Oulu was founded in 1775, Kuusamo was added to it as the northernmost municipality of the county. At the same time, Kuusamo’s old connection to Länsipohja county, whose centre was Härnosand in Sweden, ceased to exist.

Since the Middle Ages, Russia had taxed the Sámi of Maanselkä and Kitka at the same time as Sweden. Joint taxation continued even after the Finnish settlers came to Kuusamo. Danzika, the official responsible for collecting the Russian tax, arrived in Kuusamo once a year. In exchange for paying taxes, the people of Kuusamo received rights to trade and other profitable activities on the Russian side. It should also be mentioned that border peace prevailed in Kuusamo even when Sweden and Russia were at war with each other in other parts of the country. Russia in Kuusamo was represented by staarosta, the village elder who lived here permanently. Joint taxation ended in 1809, when Finland was annexed to Russia.