Author:

Ulla Ingalsuo-Laaksonen, MSSc

Riina Puurunen, Writer

Pertti Ervasti, MSc (Econ)

Translations:

Sami Mourujärvi, UAS

On the back of Reindeer pulling ahkio

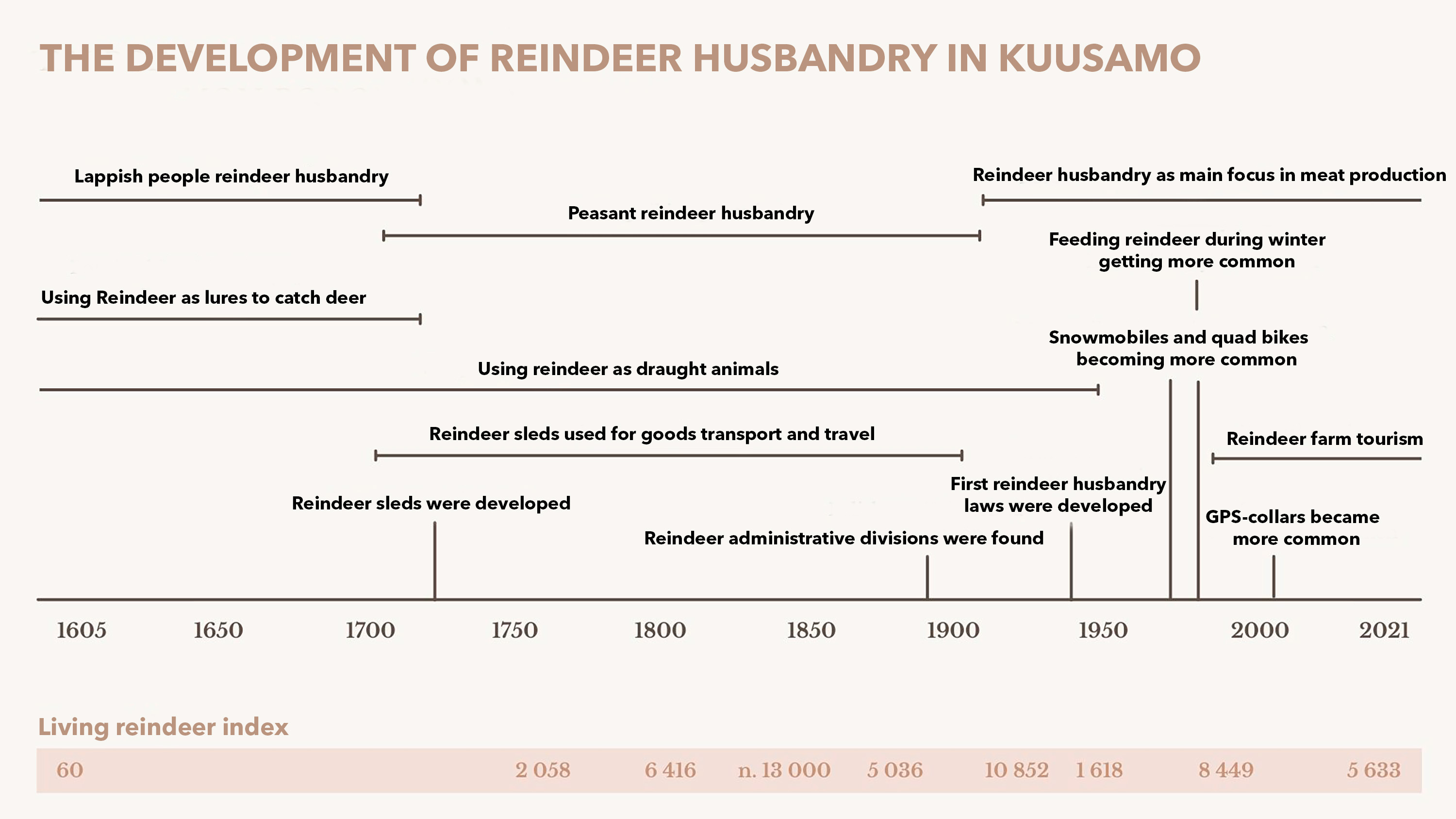

Reindeer husbandry in Kuusamo started with the hunting and taming of wild deer. In addition to deer hunting, Sámi families in the Lapland villages of Maanselkä and Kitka had few reindeer, which were used as pack and draught animals. Reindeer became meat cattle in the middle of the 18th century with the resettlement. The meat, hides, horns, and other reindeer products obtained from large herds were sold to Viena Karjala and the markets of Oulu and Tornio. Live reindeer were also transported for sale.

Large Kuusamo houses had their own ‘’pororaito’’ a chain of reindeer pulling an ‘’ahkio’’ a sled of goods. Reindeer pulling sleds transported goods from Kuusamo to the White Sea, the Gulf of Bothnia, and the Arctic Ocean. Trade was carried out on Reindeer sleds until the border closures of the 19th century. Sled transport was also important in the transportation of tar. We developed our own sled for that. Glue made from reindeer antlers, hooves and horns was also an important export product. At the turn of the 20th century, reindeer were important in logging and warfare. Reindeer were commonly used as a draught animal on farms until the 1950s.

Reindeer farming is still a viable livelihood in Kuusamo. However, its role has recently changed, as mixed agricultural economies have decreased, and farms have become more specialized. Many have chosen reindeer husbandry: which has led to the size of reindeer herds being on the rise again, even though the number of owners is decreasing. In 2022, around 80 households are engaged in reindeer husbandry in Kuusamo, and the highest number of live reindeer allowed in Kuusamo’s administrative division is 10,300.

Along with traditional reindeer herding in Kuusamo, businesses that support it are growing, such as tourism: for example, reindeer has returned to the role of a draught animal in the service of the tourism industry, and reindeer meat production is a significant part of the food industry.

From floodplain meadows to milk production

Huuhta the slash-and-burn agriculture came from Savo to the Kuusamo area with settlers. Until the mid-19th century, the focus was on slash-and-burn agriculture and the farming of grain. The goal was to be self-sufficient. Huuhta, was the main occupation of the settlers in the 18th century. In Kuusamo they cultivated, autumn rye, huuhta-turnips, oats, and potato onions. The increase in the value of forests due to the demand of sawmills caused the state to limit the use of Huuhta. The state named the slash-and-burn economy as deforestation.

Especially in the 1860s the ban on slash-and-burn agriculture led to a shortage of grain and years of famine. The focus of agricultural production changed to the farming of livestock. Important additional sources of livelihood for the rural population were carriage conveying, fishing, hunting and reindeer husbandry. The money for the purchase of grain was obtained by trading butter, fish, reindeer skins and reindeer meat. The export destinations were cities of Oulu and Tornio, and neighbouring countries of Norway and Russia.

Efforts were made to increase the meadow area by draining the waters of lakes and damming the marshes into floodplain meadows.

The supply of livestock feed from marsh and coastal meadows came to an end and sowing of grass became more common from the 1930s. After the great partition took place in the early 1950s livestock feeding was transferred from the forests to the pastures bordered by the electric shepherd. Agriculture began to mechanize and develop strongly.

A Cooperative Dairy which refined and marketed the dairy products was founded in Kuusamo in 1951. The development continued strongly until the end of the 1960s, when agriculture began to be driven down due to national overproduction: dairy farming was stopped, and a premium was paid for slaughtered cows. Smaller farms lost their livelihoods, and a major relocation began, which drove thousands of workers from Kuusamo to work in southern Finland and Sweden.

Those left on their farms developed their agriculture into dairy and beef cattle farms. Milk production is still one of the most important parts of agriculture in Kuusamo – as the number of farms decreases, their size and production increases. Most of the raw material for Finland’s northernmost cheese factory, ‘Kuusamon Juusto’, comes from the surrounding area.

The owners did not guess where the road would lead over the decades when they founded the ‘Kuusamon Osuusmeijeri’ co-operative in 1951. At the co-operative’s meeting, it was decided that the products would mostly be received as cream. Only the amount needed for local consumption was collected from the surrounding area as milk. In the early years, the focus was on butter production.

The reception station made it possible to consolidate dairy operations. In December 1953, it was stated that the quantities of cream and milk were at the level required to build our own dairy. In the between the summer and fall of 1954, a plot of land for the dairy building was bought from the municipality of Kuusamo, and construction work began in cooperation with Valio (Valio Ltd is a Finnish manufacturer of dairy products).

Already after four years from the construction of the dairy, the premises were found to be too small. With the expansion works, a cheese factory was completed for the dairy. The first cheese was made on 10th of August 1961, when 6 cheeses were made.

At the end of 1963, it was decided to terminate the 20-year lease agreement with Valio before the set date. This started the journey as a dairy under the name of Kuusamon Osuusmeijeri. The 1960s and 70s were a time of powerful reform. Dairy economy flourished and the dairy did well.

Various products were manufactured until 1989, when the packaging of both butter and milk was stopped in Kuusamo. Instead, the utilization of whey produced from making cheese began. In 1995, the construction of their own whey processing plant began. Further processing of powders has developed enormously over the years. Today, cheese whey is further processed by drying it into protein powder and lactose.

The beginning of the 1990s brought many difficulties for the profitable dairy operations and the threat of ending the processing operations in Northern Finland. Under the leadership of Managing Director Jouko Juntunen, the dairy’s administrative made a unanimous decision to maintain dairy operations in the ‘Koillismaa’ the Northeastern Land. Since Kuusamon Osuusmeijeri had traditionally invested in milk processing, a partner whose operation needed cheeses and powders and who had sufficient resources to create a nationwide operation had to be found. In the summer of 1996, Kuusamon Osuusmeijeri founded the processing company JK Juusto Kaira Oy in cooperation with Ingman Foods and Ranuan Meijeri Oy.

With the new processing company, the production of cheeses and powders was centralized in Kuusamo. The production of butter and special products continued at Ranua. The processing and collection of milk was transferred to Juusto Kaira, and under the name Kuusamon Osuusmeijeri, milk procurement, producer advice, producer training and the development of producer services were continued.

The current millennium has been a time of expansion. In 2002, the cream cheese line was completed and production of Pohjanpoika cheese began.

At the beginning of the decade, a lot happened at the factory: Arla Ingman’s butter cheese production moved to Kuusamo. At the beginning of 2012, a new smoking equipment was also put into use for our own smoked cheeses.

However, later that year, Arla Foods made the decision to end cheese production in Finland. The future of the cheese factory seemed uncertain, but the milk producers from Koillismaa area of Finland wanted the cheese production to continue in Kuusamo. So, the Kuusamon Osuusmeijeri family farms claimed the cheese factory for themselves. The cheese factory was named ‘Kuusamon Juusto Oy’ – and that name is proudly carried in Kuusamo even today.

In 2016, due to the tight economic situation, both Kuusamon Osuusmeijeri and Kuusamon Juusto applied for corporate restructuring. It was not possible to buy enough milk for the needs of the cheese factory. That crisis was also overcome, and today Kuusamon Juusto employs more than 70 cheese-making professionals in Finland’s northernmost cheese factory and annually processes the milk produced by about 150 dairy farms into cheese and the resulting whey into powder.

Clear water fish from Koillismaa

Kuusamo’s wealth of water with its rivers and large lakes create good conditions for fishing. Fishing was already a significant means of livelihood for the Lapland population of the area. Fishing in the area was especially practiced by the people of Ii and Pudasjärvi before the arrival of new settlements during the 16th and 17th centuries.

Next to agriculture, fishing developed into the second most important livelihood for the people of Kuusamo. The main tools for fishing were nets, seines, and fyke nets. Fishing was practiced to the extent that fish was also taken to the markets in Oulu and Viena. At the end of the 19th century, 1,500–1,700 people participated in fishing, and almost 500 vendace seines were in use.

In the 1960s, rainbow trout farms and their industrial processing further was established. The processing also utilized wild fish.

Kuusamo’s vendace ”Kitkan Viisas” is known throughout Finland. According to tradition, the small and wily fish got its name from the fact that it does not swim along the rivers flowing east to Russia but stays in the large clear-watered lake of Kitka.

In the 21st century, through product development, further processing of fish has developed into a significant industry in Kuusamo. There are a couple of dozen professional fishermen working in Koillismaa.

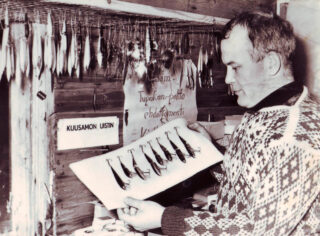

Kitkan Viisas was the beginning of Kuusamon Uistin

‘Kuusamon Uistin’ a fishing supplies store which grew into an international brand, was founded by neighbours Paavo Korpua and Paavo Putila from their willingness to work. It was the 1960s and there was a shortage of work, so they had to come up with something new. The company’s first hit product was a wobbler called Kitkan Viisas. Founded in 1967, the beginning of the company was modest, but the belief in the cause and know-how was strong. Korpua was an educated watchmaker and Putila was an electrician. The first lures were made in the back room of the barn building freed from the laundrette in Korpua.

Kitkan Viisas was a foldable balsawood wobbler. It was fished extremely well and more trade began to take place. More space was needed, and a disused forest work cabin was bought. The selection included metal lures, ice-fishing lures, and knives.

For the first ten years, production was in temporary premises. Now Kuusamon Uistin owns two modern factory buildings along Finnish national road 5 in Kuusamo. There is also a cafe and a factory store connected to the factory.

Kuusamon Uistin has about 80 own products, with several size and colour combinations. The selections include metal spoon lures, Kuusamo spinnerbaits, various vertical and balance lures for winter fishing, as well as mormuska-type lures, ice-fishing rods and wilderness bonds. Kuusamon Uistin manufactures two of Finland’s oldest lure brands, Räsänen seiska and Professori. Räsänen has taken its first forms in Utsjoki and Professori in Vyborg.

Kimmo Korpua, son of Paavo Korpua, continues to manage the company. Kuusamon Uistin employs around 30 people in the community.

Tight-grained northern wood

Forestry in Kuusamo has its roots in tar burning in the 19th century. Tar was mainly produced in Southern Kuusamo and was transported to Oulu and White Sea.

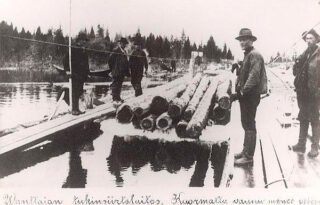

The use of wood for more than household purposes began in the second half of the 19th century. Most of the logs for sawing were floated through the Iijoki watercourse, but also to the White Sea along the rivers of Savina, Avento, Kitka and Oulanka. The trees gathered in Paanajärvi, from where they were floated along the river Oulanka to the sawmills on the seashore. Sawn timber was taken by sea across the Arctic Ocean to England.

Due to the merits of the waterways, the ‘savotta’ logging and timber rafting provided a living for those with small farms and those without a farm. The value of Pitäjä’s forests also comes forward in the fact that logging companies from Russia and Sweden were also logging there. In addition to Finland, they brought workers to Oulanka’s savotta and timber rafting from Sweden and Russia.

The First World War closed the border between Finland and Russia and the timber rafting to the Russian side ended. The difficulty of transporting wood and the ambiguities related to land ownership ended the forestry utilization of Oulanka. Thus, the financial interest that was an obstacle to the establishment of Oulanka National Park gave way and the nature conservation values emerged more and more clearly.

Few sawmills operated already in the 19th century locally in Kuusamo. These sawmills were connected to the mills and whetstone factories built on the local rapids. The great partition that was interrupted in the 1920s and the depression of the 1930s reduced logging, and the sawmill industry recovered very slowly after the depression. The first local steam saw ‘Kuusamon Puu’ -company started in the parish village, on the shores of Lake Kuusamojärvi right after the war.

Farmer Erkki Virranniemi founded Pölkky Oy in 1968. Today, the family business Pölkky is the largest private wood processor in Northern Finland and a significant employer in several locations. Pölkky has production facilities in four locations, and the company exports its products to 35 countries. The villa and house factory ‘Kuusamo Hirsitalot Oy’, founded by Simo and Arto Orjasniemi and Antti and Jouko Virranniemi, supplies log house packages to Finland and for export. The slow-growing, tight-grained wood in the North is a valued raw material all around the world

Kuusamo’s collective forest is the largest in Finland

Founded in 1956, Kuusamo collective forest is Finland’s largest and most important player in the Finnish timber trade. The area of the collective forest is approximately 93,100 hectares, of which almost 65,000 hectares are forest land. More than 4,100 share farms and the annual growth of trees is about 219,000 cubic meters.

The forests of the Kuusamo collective forest are in Kuusamo, Suomussalmi, Taivalkoski and Posio. Collective forests are private lands and have no public law character or obligation. The main business is producing and selling wood. In addition, the collective forest rents out different usage rights from its land areas and sells hunting rights and land materials.

Is it a good whetstone year?

In Kuusamo, also called Liippapitäjä, whetstones had already been quarried in the 18th century. The first Kuusamo hones were made in Kitka from natural stone. Later, the makers of the hones were found in the areas of Suininki and Vuotunki, closer to the Laajusvaara slate deposit.

In Kuusamo, the hones became the most prominent local craft in the 19th and 20th centuries. A few houses produced hones to be sold in the cities. The industrial production of grinding stones began in 1913 at Kuusinki’s Jyrkkäkoski, later also at Saunakoski and Suininginkoski. Locally important sawmills, mills and planers also belonged to the milieu of the hone factories.

Hones were transported as far as Oulu and Central Europe, and floor stones were transported to, among other things, the circular hall of the parliament building. In the late 1930s, factory-made hones supplanted natural stone hones. The Jyrkkäkoski hone factory operated under the name Kuusamon Kivi Oy in 1932–1948 and as Kuusamon Kovasin Oy in 1946–1949.

In addition to scythes, knives, axes, chisels, and knives are sharpened with Kuusamo’s hones.

Water and ‘härkin’ style mixer mills were common in various parts of Kuusamo in the mouths of streams and rivers starting from the 18th century. Practically every village had its own small mill. Härkin-mills had to be taxed, unlike windmills, and therefore the smallest mills were often located far away, hidden from the eyes of tax collectors.

In the härkin-mill, the water rotates the vertical wooden blade, i.e. the härkin, which in turn rotates the upper stone. Both the rock and the log were spinning at the same rate dictated by the force of the flowing water. A planer, a saw and later an electric generator could also be connected to Härkin-mill. Often, the village’s first electricity was obtained from the Härkin-mill.

In Härkin-mills, the owners milled the grains themselves until the 1950s, when Kuusamo’s first combustion engine powered mill started at Lahdentaus, Kuusamo. The mill founded by Hannes Pölkki milled until 1998.

One of the oldest härkin-mills in Kuusamo was in Vuotunki, from where the mill built in the 1730s was moved and renovated to the Kuusamo home region museum in the 1970s.

There have been mills in Kuusamo, for example Oivanki’s mill in Kotijoki, Myllykoski’s mill in Juuma, Niskala’s mill in Pyhäjoki, Rontti’s mill in Rysäjoki, Aparainen’s mill in Penikkajoki, Oijuskoski’s mill in Oijusluoma and Jokilammi’s mill.

The heritage of the Viena trade road

For centuries, Kuusamo was the crossroads of the trade route between Dvina Bay and Gulf of Bothnia. The people of Kuusamo rented boats and barns to merchants, and sold game, fish, butter, and meat. Kantokylä with customs stations was a trading center until the end of the 19th century.

After land trading was allowed, the first trade shop was established in Kirkonkylä in 1869. Juho Turpeinen was involved. Previously, you could only trade in cities, but according to the new regulation, you could also set up a shop in the countryside. However, in Kuusamo, for centuries, houses had been doing trade without regard to the law. By the standards of the time, the requirements for establishing a store were tough, especially in the north. A merchant had to know how to read, write, calculate, and manage accounting. Due to the weak school system in the north, the establishment of shops in the villages did not cause a great rush.

At the beginning of the 20th century, there were already seven permanent shops in Kuusamo. A special feature of the area was the transit trade with the Karelians from Viena. Several of these merchants later established permanent stores in other parts of Finland as well.

Kuusamo Osuuskauppa was founded in 1906. The cooperative grew with its branch stores into Koillismaan Osuuskauppa in 1985.

The first specialist shop, Reino Tammi’s watchmaker’s shop, was opened in Kuusamo in 1936. The heritage of the old marketplace is carried in its name by Bjarmia Oy, which has been manufacturing and selling ceramics in Kuusamo since 1974. Fishing traditions are cherished, and the industry is renewed by Kuusamon Uistin Oy, founded in 1967, which has grown into a globally known brand.

Entrepreneurship is about being able to keep going, no matter how hard it gets, says Aini Valkama, who founded the ceramics company in Kuusamo in 1974. There have been trials, but it has been successful, because the belief in one’s own skills and self-made has carried Bjarmia through the decades.

The Kuusamo handmaking tradition is now being continued by the next generation: since 2008, daughter Kaisa Valkama-Kettunen has been the CEO. During her time, the company has also opened a store in Helsinki and created export connections to Japan.

The ceramics company got its name from the Bjarmen: it was a trading nation that mainly influenced the White Sea region, whose culture flourished in the period between the Viking expeditions and the Crusades. These fur trappers and artisans roamed the North more than a thousand years ago, trading their products all the way to Norway. They stayed in the Kuusamo area for a particularly long time – as has Bjarmia.

Over the years, there have been a lot of whims and fortunes. As a young entrepreneur, Aini Valkama started selling the ceramic mugs and soup cups she made, and the onion bags crocheted by Kuusamo housewives to Stockmann. In the early days of travel, the word onion was also embroidered on the bags in English and German.

– While sitting in the purchasing manager’s room, I realized that the mug looked like a murder weapon and, on top of that, it was broken. The gentleman looked at what I brought for a while and happily stated that in Kuusamo they know foreign languages! Then bought our product and launched the soup cup as a French onion soup bowl. We worked together for decades after that.

– The worst place for us was one year under Christmas, when we were waiting for a new oven. The order book was full, and the dishes were ready to be fired. The expectations were enormous. However, the oven that was coming from Denmark fell from a crane in the port and was broken beyond use. We didn’t get a new oven until spring. That season was gone.

Bjarmia’s strong women are inspired by the nature of Koillismaa. The company’s ceramics reproduce hazards, trees, and seasons. The products are designed to be beautiful and showy, but above all to be used.

– I believe that the appreciation of Finnish ceramics and craftsmanship will hold its ground. We have not started producing our ceramics elsewhere, but we want to keep the production in our own hands here in Kuusamo, says Kaisa Valkama-Kettunen.

From Paanajärvi via Ruka to Oulanka

Artist Akseli Gallen-Kallela’s visits to Paanajärvi fuelled the already awakened interest in Kuusamo’s landscapes. The road built in the middle of the 19th century via Vuotunki to Paanajärvi was kept in good condition for tourists, the ‘kestikievari’, taverns with licenses for rides to another similar tavern, were successful and the first Travelers’ Homes were established in the 1930s.

The growth of winter tourism began when the first ski slopes were cleared in arctic hill ‘Ruka’ in 1954. Before that, there had already been skiing on forested slopes and admired the scenery from the top of Ruka. ‘Rukakeskus Oy’, a family company founded by Juhani Aho, has been responsible for Ruka’s slope operations since 1973. Regular air traffic to Kuusamo had started a year earlier. The year-round and international Rukakeskus Group is one of the leading tourism companies in Finland. Program service companies landed at the tourist center in the 1980s and have established their place in the center’s service offering. The number of places to stay and overnight stays increases every year.

The cornerstone of nature tourism in the nature city is Oulanka National Park. Kuusamo’s several nature sites and comprehensive routes promote the number and growth of nature tourism and nature well-being companies.

The importance of cultural tourism has grown in the 21st century and has provided an opportunity for numerous small tourism operators: tourists are now looking for authentic Kuusamo and the atmosphere of the old days.

”Had to operate, would die on the way anyway”

Initially, only one method of hospital treatment was known in Kuusamo: to send the sick person to the county hospital in Oulu, if home treatment and the old folk healing methods did not work. Medicines were also delivered with the cargo from Oulu. However, isolation rooms for suspected epidemic diseases had been organized for a long time. At the beginning of the 19th century, Lieutenant Johan Wilhelm Stjernecreutz was the first to administer vaccinations in the region.

When Pudasjärvi got its own doctor in 1859, the people of Kuusamo also started requesting their own. From 1871, requests were made every few years and eventually they were agreed to. The first midwife was hired in 1889 and at the same time the midwife took over the vaccinations. However, the first midwife, Maria Nyqvist, got tired of the huge workload and her successor, Hanna Aaltonen, wasn’t hired until 1894.

The first pharmacy in Kuusamo was established on 6th of December 1892, when Karl Arrhenius, a pharmacist from Pudasjärvi, opened a side pharmacy in a house rented from the merchant Antti Pitkänen, located near the church. The pharmacy became independent in 1909 and pharmacist Matias Arthur Valentin Kronqvist became its pharmacist. The pharmacy burned down as a result of a fatal spirit barrel explosion in 1911. The pharmacy maid was burned to death in the accident and the pharmacist was so traumatized that he soon fell ill and died. Pharmacist Rudolf Alarik Torckell arrived as the new pharmacist.

In 1900, the state established three regional medical districts in Northern Finland, of which Kuusamo was one. Licentiate of medicine Heikki Huovinen arrived as the first doctor shortly after the establishment.

Kuusamo’s Hospital was built in 1906 with the help of state aid, when 15 infirmaries and a nurse’s position were added. Juho Warpula took up the post of regional doctor around that time. In 1921, Ali Ervasti was appointed as the regional doctor. In addition to Kuusamo, Ervasti treated the patients of Posio and Taivalkoski and often had to perform demanding surgeries, because the journey to the Oulu County Hospital was long and made difficult by the sick. ”You have to be cut, you’ll die on the way anyway,” stated Ervasti often laconically.

The hospital in Kuusamo was destroyed during the wars after German and Russian troops burned down the church village of Kuusamo and the hospital was distributed in several buildings. The regional hospital became a municipal hospital, and the regional doctor became a municipal doctor in 1950. The new municipal hospital was completed in 1952, where two municipal doctors worked until the 1960s, when the hospital was expanded to 100 beds, a new surgery department was built, and the posts of the municipal doctor were increased. Around the same time, the first post of surgeon was established in Kuusamo.

With the public health act that came into force in 1972, the name of Kuusamo municipal hospital changed to Kuusamo health center. In the 1980s, Raatesalmi’s psychiatric treatment center was transformed into the psychiatric department of the health center. In 2008, births in Kuusamo were stopped and concentrated in Oulu. Currently, the Kuusamo health center has 20 doctor’s positions, weekly surgeries, and specialist medical services in several different fields.

People and goods travel on rubber wheels

The railway has been in the dreams of the people of Kuusamo since the 19th century, but so far in vain. The first wishes regarding the Kuusamo railway line were expressed already when the Ostrobothnia railway line was completed in 1883. As road transport increased in the Oulu–Kuusamo–Paanajärvi direction in the 1890s, a railway was planned from Oulu via Kuusamo all the way to the shore of the White Sea. Railway plans were particularly prominent in the 1920s and 1930s. The main goal at that time was to connect the operator to the state railway network.

The wishes did not come true, so focus was on rubber wheels.

The first mail car started operating on the Oulu-Kuusamo line in 1921. However, the mail car was not enough to transport the rapidly growing freight traffic, so more robust operators were needed.

Viljami Kantola, who has been driving a taxi since 1945, founded his own transport company in Kuusamo in 1960. The idea was originally from Elvi Kantola, who worked in the Kuusamo office of ‘Pohjolan Liikenne Oy’, a transport company, from 1955–60 and at the same time noticed the need for transport between Kuusamo and Helsinki.

Kantola started freight liner service to Helsinki, transporting export cheeses from Kuusamo Osuusmeijeri. The first bus license for Kantola was granted in December 1960 and it was entitled to operate with one truck twice a week from Kuusamo to Helsinki. In September 1962, operations could be expanded when the ministry granted Kantola a line permit from Kuusamo to Oulu. The third freight line was obtained when the ministry granted a line license for the route Kuusamo-Oulu-Helsinki in March 1965.

The company began to grow and in 1973 the fleet already included five combination vehicles and three lighter delivery and service trucks. After Viljami Kantola died in 1980, Elvi Kantola continued to operate under the name ‘Kuljetusliike E. Kantola’.

Along with Kantolas, Koramos developed professional traffic. In 1951, Sulo Koramo bought a Ford Rhein shared with Niilo Säkkinen. The car was transporting gravel to a new power plant site at Jumisko, Posio. The construction of the Finnish national road 5 also offered work later. In 1953, Sulo Koramo bought a Dodge brand truck that was used to drive pulpwood to the Rauma, Repola factory in Oulu.

In 1967, timber was driven to the Virranniemi sawmill (owned by Pölkky Oy) located in Kantojoki. The eldest of Sulo’s sons, Jouni and Jorma Koramo, joined the company’s operations in 1968, and in the same year they started driving timber for Kuusamo’s collective forest. In 1973, another car was bought, and the general partnership ‘Veljekset Koramo’ was founded. Jouni, Jorma and Jukka Koramo were involved in the operation, and later in the late 70s the brothers Jouko, Ossi and Jyrki joined the operation.

In 1982, the Koramo brothers bought a stake in Kantola and the operations were combined. The name of the company became ‘Kuljetusliike Kantola & Koramo Ay’. In 1992, the Koramo brothers bought Kantola’s share in the company and the corporate form was changed to a limited company.

Since then, the company has expanded its operations to Kuopio, Southern Savonia and North Karelia. Today, the third generation is already involved in the operation.

Air traffic to Kuusamo started in 1972, when the first air traffic control building was commissioned. The project managers were Jorma Kantola and Jaakko Perälä. There was great joy when the scheduled service between Oulu and Kuusamo finally started. The passenger terminal was completed in 1988, the runway was extended to 2,500 meters in 1997, and in 2005 Kuusamo Airport received international airport status. Every year, approximately 100,000 passengers fly from Kuusamo to the world and back.

A postal car on its way from Oulu to Kuusamo in the winter of 1935.

Photo: Finnish Postal Museum.

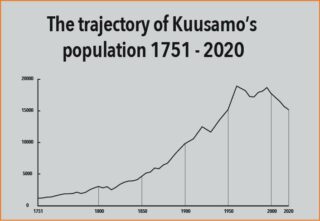

In the beginning there were only a small group here: Kuusamo’s population was only 615 in 1718, but a couple of decades later there were already more than a thousand people. In 1751, there were 1,208 residents in Kuusamo. Population growth continued steadily, although high mortality rates taxed the population in the early 1780s. The population loss was caused by four consecutive drought years and the smallpox epidemic that followed them.

However, thanks to the high birth rate, Kuusamo’s population grew so that at the turn of the century there were more than 3,000 Kuusamo residents. The years 1800 and 1802 were bad loss of crop years and the mortality rate at that time was 40 percent of the areas inhabitants. In 1880, the number of inhabitants had increased to 6,750, and in 1900 there were already 9,813 inhabitants. The population decreased momentarily in 1926, when Posio became an independent municipality.

Kuusamo’s population was at its highest in the rich early 1960s, when the number of Kuusamo residents was at 18,919. With the great migration, the population began to decline rapidly, but reversed itself in the 1980s. In 1995, there were more than 18,687 Kuusamo residents again. From the end of the 1990s, the population of Kuusamo has decreased until 2019. In 2020, the population of Kuusamo was at 15,209 which was 75 residents more than the year before.

In reality, Kuusamo has significantly more people than the official population. It is estimated that at an average of 5,000 more people stay overnight in Kuusamo: the vast majority of them staying in cottages or being remote workers from nearby areas.

Author:

Ulla Ingalsuo-Laaksonen, MSSc

Riina Puurunen, Writer

Pertti Ervasti, MSc (Econ)

Translations:

Sami Mourujärvi, UAS