In accordance with the conditions of the peace treaty that ended the Continuation War (1941–44), Finland was obliged to cede parts of her land to the Soviet Union. A fifth of the Kuusamo area was ceded, and some 2100 Kuusamo residents lost their home villages. The largest of these were Paanajärvi, Tavajärvi and Vatajärvi, the smaller ones were Siikajärvi, Enojärvi and Kenttijärvi.

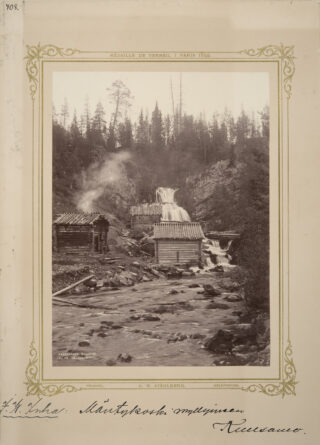

The 24-km long canyon lake Paanajärvi has the greatest scenic value in the area. The most famous sights there are Ruskeakallio cliff and Mäntykoski waterfall. The fells Nuorunen and Ukontunturi stand mightily on the east side of Tavajärvi. Other well-known sights are Kivakkatunturi fell and Kivakkakoski rapid, located near the former Karelian village Vartiolampi.

The first Kuusamo residents settled in Paanajärvi in the late 18th century. In the early 19th century, they bought the lands of this border region from their Viena Karelian neighbours. Animal husbandry, farming, fishing and hunting, and also tourism and trade made the area prosperous.

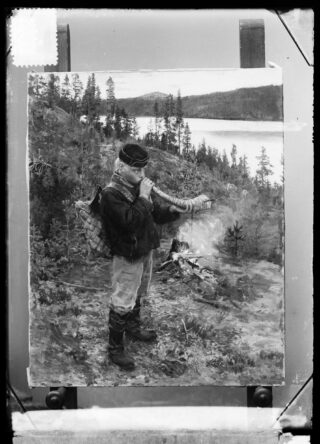

Paanajärvi gained national recognition through the paintings of Akseli Gallen-Kallela. The best-known of them are Shepherd Boy from Paanajärvi, Great Black Woodpecker and Mäntykoski Waterfall. I.K. Inha photographed the sceneries of the area for the national catalogue. Gallen-Kallela and Inha worked in Paanajärvi in summer 1892.

Today, neither Paanajärvi, which belongs to Russia, nor the entire ceded area is permanently inhabited, but traces of the old Kuusamo settlement are still visible. In 1992, Paanajärvi National Park was established in the area. It is located near Oulanka National Park on the Russian side of the border.

In 1980, The Paanajärvi-Tavajärvi Society was founded to cherish the memory of the villages in the ceded area of Kuusamo, and to improve the opportunities for people to know their roots.

”Generations of longing whispering inside me”

– Veikko Aittakumpu

”I witnessed a storm. I can’t remember whether it was called soili or mauri, but I remember the trees. They bent in the wind like blades of grass. Many a tree fell, many broke their roots. Those trees died. The great storm that started on 30 November 1939 damaged, if not severed, the roots of many people. The loss of your home region is heavy to bear.”

– Maija Alajuuma

Aerial photo of Paanajärvi village in 1927. Farmhouses surrounded by their fields are located by the lake.

PHOTO Ahonius, Finnish Forest Association Collection, Metsätaloudellinen Valistustoimisto

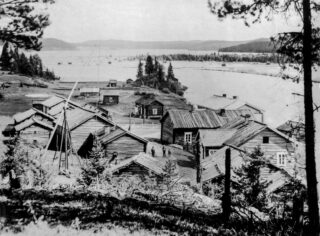

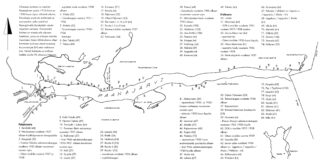

Photo from the western end of Lake Paanajärvi to the east. The settlement was centred at the western end of the lake, where River Oulankajoki flows into Lake Paanajärvi. There were farms along the lake all the way to the national frontier. Most of the farms were located on the sunnier northern shore. Before the last wars, there were 88 farms in Paanajärvi, 68 in Tavajärvi and Vatajärvi, 7 in Siikajärvi, 33 in Enojärvi and 7 in Kenttijärvi.

PHOTO Kinnunen Archive

Antti and Anna-Riitta Pesonen are cutting grain at the Paana fields. The calcareous cliffs surrounding Lake Paanajärvi shores, and the warm, south-facing shore fields created favourable conditions for agriculture. Barley, rye and oat were the most important crops, but wheat was also grown on an experimental basis. The area was not sensitive to frost, because the lake, at times almost 130 metres deep, served as a radiator well into the autumn months. The situation was different after the wars, when the Paanajärvi evacuees were settled in so-called cold farms to ditch and clear swamps into fields. Many a time the migrants longed to be back in their lost home farms, on the shores of the lake so rich with fish.

KUVA Pietinen, Historian kuvakokoelma, Museovirasto

In 1892, Akseli Gallen-Kallela worked in Paanajärvi from August until the end of October. Travelling in wilderness conditions, Gallen-Kallela sought new forms of expression as a painter, moving from realism into symbolism. For instance, there were several experimental versions of the painting Mäntykoski waterfall. The model for Shepherd Boy from Paanajärvi was Antti Pesonen, 13, from the Paana farm. An important task for shepherd boys was to walk with the cattle in the woods and, by tooting the horn, frighten away predators such as bears that prey on domestic animals. Later, Antti Pesonen and his daughters worked as mail carriers from the western end of the lake to the eastern end. The easternmost houses in Lake Paanajärvi near River Astervajoki (aka Mutkajoki) were Arola, Lahtela and Talvela.

PHOTO Daniel Nyblin, Finnish National Gallery Archive Collections

In summer 1892, photographer K. E. Ståhlberg hired I. K. Inha to photograph the nature of northern Finland. On his first trip to the north with 80 kilos of photographic equipment, Inha also visited Kuusamo. The photographs Inha took in Paanajärvi, River Oulankajoki, the Nuorunen fell and at Kivakkakoski rapid on the Russian side of the border have become classics of Finnish landscape photography. This picture shows a mill in Mäntykoski rapid, Paanajärvi, in 1892. One of the buildings is a mill sauna.

PHOTO I. K. Inha, Ethnographic Picture Collection, Finnish Heritage Agency

The road to Paanajärvi via Paljakka, Vuotunki, was completed in 1925. At first, the road ended at the Manninen house on River Oulankajoki, where the river had to be crossed by ferry. There was a ferryman’s cabin at Alatalo across the river. Later in the 1930s, the road was continued to Sovakylä village, and from there on via Käylä village to Kuusamo parish village. This formed a circle route that was called ”karhunkierros” (bear trail). Kuusamon Osuuskauppa Co-op started carrying people and freight regularly on this route using a combined bus and lorry called “sekajuna” (mixed train).

PHOTO Kinnunen Archive

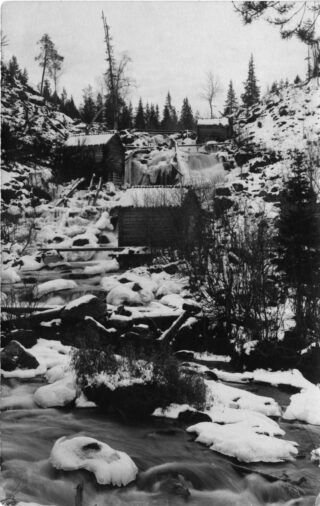

Buildings at Selkäkoski rapid. The rapid powered both the mill and the sawmill. River Selkäjoki flows from Lake Selkäjärvi in the south down to the middle section of Lake Paanajärvi.

PHOTO Kuusamo Local Heritage Association Picture Collection

This picture is from a photo album compiled by Martta Liesi (née Kakko). The woman in the picture is possibly Martta Kakko herself. She studied in Vyborg to become a nurse and a district nurse. For about 8 years in the 1930s, Kakko worked as a district nurse at Paanajärvi village hospital. During Winter War she worked as a nurse at the Petsamo dressing station. After the wars, she worked as an occupational health nurse at the dairy company Valio.

PHOTO Martta Liesi (née Kakko) Photo Archive, Helsinki University Museum

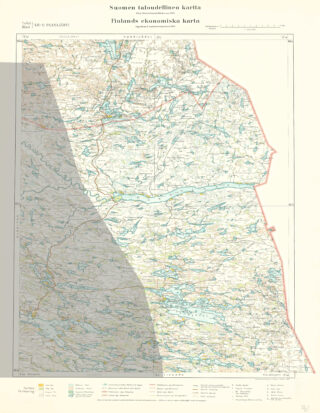

A map sheet of an economic map from the north-eastern part of Kuusamo in 1925. In the middle of the map there is the long and narrow Lake Paanajärvi. Below it is Lake Tavajärvi with its many islands, and behind the lake are the fells Ukontunturi and Nuorunen. The light-coloured area was ceded to the Soviet Union after the last wars.

PHOTO National Board of Survey (Finland)

The picture shows timber floaters at Kivakkakoski rapid, near the village of Vartiolampi, inhabited by Karelians. The Kivakkakoski rapid is one of the most spectacular rapids in River Oulankajoki. From Kivakkatunturi fell in the background, great views open over the big eastern lakes of Pääjärvi and Tuoppajärvi.

Starting from the late 1900th century, Swedish and Russian forestry companies carried out extensive logging in the area along River Oulankajoki. The logs were floated to Lake Paanajärvi and from there all the way to sawmills on the White Sea coast.

PHOTO Kinnunen Photo Archive

Antti and Anna-Riitta Pesonen are cutting grain at the Paana fields. The calcareous cliffs surrounding Lake Paanajärvi shores, and the warm, south-facing fields created favourable conditions for agriculture. Barley, rye and oat were the most important crops, but wheat was also grown on an experimental basis. The area was not sensitive to frost, because the lake, at times almost 130 metres deep, served as a radiator well into the autumn months. The situation was different after the wars, when the Paanajärvi evacuees were settled in so-called cold farms to ditch and clear swamps into fields. Many a time the migrants longed to be back in their lost home farms, on the shores of the lake so rich with fish.

PHOTO Pietinen, Historical Picture Collection, Finnish Heritage Agency

A fiord-like view west of Mäntyniemi. The Mäntyniemi farm was located on the north shore of Lake Paanajärvi, near the east end of the lake. Like the Rajala house, Mäntyniemi used to be a favourite way station for Finnish traders and Russian peddlers. The estate comprised two resident buildings and several outbuildings owned by the Leinonen brothers and their families. Elias (Mänty-Ella), one of the brothers, was one of the most famous bear hunters of Kuusamo. He had been involved in the killing of over 20 bears. In summer 1892, Mary Gallen-Kallela had nursed the older farmer Aatami Leinonen, after he had been badly mauled by a bear.

PHOTO I. K. Inha, Ethnographic Picture Collection, Finnish Heritage Agency

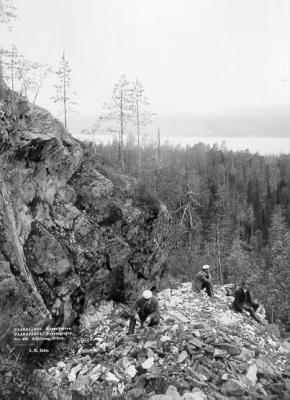

A quarry in Kuparivaara (Vaskivaara) hill (copper hill), opposite of Rajala and Paana, photographed by I. K. Inha. The quarries were blasted with gunpowder charges by Fredrik Planting, police chief of Kuusamo, and Johan Käkelä. Planting, together with Käkelä who came from Vuotunki village and had been trained as a gold digger in Siberia, started prospecting for Lapland gold in Kuusamo, with no significant results.

In 1892, writer, journalist and historian Santeri Ingman (later Ivalo) wrote in his travel book that the Paanajärvi people were accustomed to travellers and eagerly told them the way to the sights. Ingman went to see the Mäntykoski rapid, the Ruskeakallio cliff and the ”copper mountain”. He felt that due to the excessive praise from the locals, the famous sights had not entirely met his expectations.

PHOTO I. K. Inha, Historical Picture Collection, Finnish Heritage Agency

The road to Paanajärvi via Paljakka, Vuotunki, was completed in 1925. At first, the road ended at the Manninen house on River Oulankajoki, where the river had to be crossed by ferry. There was a ferryman’s cabin at Alatalo across the river. Later in the 1930s, the road was continued to Sovakylä village, and from there on via Käylä village to Kuusamo parish village. This formed a circle route that was called ”karhunkierros” (bear trail). Kuusamon Osuuskauppa Co-op started carrying people and freight regularly on this route using a combined bus and lorry called “sekajuna” (mixed train).

PHOTO Kinnunen Photo Archive

From 1931 to 1935, the first border-region pastor in Kuusamo was Toivo Laitinen. He served as an officer in the Winter War and the Continuation War, and later worked as Chaplain General from 1956 to 1968. In 1935, Toivo Laitinen’s brother Olavi Laitinen carried on the work of the border-region pastor. The Paanajärvi border church was completed in 1936 and consecrated in 1937. After the wars, the border church was built to Käylä village.

PHOTO Kinnunen Archive

In the 1930s, before the wars, Paanajärvi was a prosperous village. The estate of Kauppila Inn was located in the west end of Lake Paanajärvi. In Paanajärvi, tourists were also accommodated in the Finnish Red Cross village hospital, founded in 1927, and in an inn, opened in 1937, which had five bedrooms and a dining room. Other services were provided by four shops and a Lotta kiosk. In 1935, there were 720 inhabitants in Paanajärvi.

PHOTO Kinnunen Archive

The rugged wilderness of Lake Paanajärvi shown in a photograph taken by Esko Suomalainen in 1935. Mutkatunturi fell rises up to a height of about 450 metres in the eastern part of the lake.

PHOTO Esko Suomalainen, KKSA

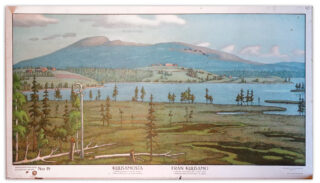

A picture of a primary school educational poster, with Lake Tavajärvi in the foreground and Ukonvaara fell in the background. Nuorunen, the highest fell in the area, is located south of Ukonvaara fell, behind Lake Tavajärvi. The educational poster was painted by Vihtori Ylinen in 1915.

Tavajärvi School was the first school built outside Kuusamo parish village. It was founded in 1894.

KUVA Anita Koljonen, teos Kuusamon siirtoväki, 1983

Ville Hänninen (aka Siika-Ville), who lived in Siikajärvi, crossed the border to the Russian side with his reindeer buck to do trading.

KUVA Anita Koljonen, teos Kuusamon siirtoväki, 1983

Aatami Tauriainen (aka Kentti-Ukko) making fish traps in Kenttikylä village. The village comprised a cluster of seven houses right by the Russian border. The village was truly remote, as the only way there was a 30-km footpath from Lämsänkylä village.

Kalle Määttä, who worked as a consultant of Talousseura (Agricultural Society) and later as the governor of Oulu Province, has told about a peculiar way of feeding a child he saw in Kenttijärvi: above the cradle there hung a teat from a cow’s udder, from which the child sucked milk.

PHOTO Anita Koljonen, in her book Kuusamon siirtoväki (The Resettled of Kuusamo), 1983

In Nurmela, Paanajärvi, the old and young farmwives working on the farm during the Continuation War in June 1943.

PHOTO Aukusti Tuhka

Mother and children in front of their new building during the Continuation War in Manninen, Paanajärvi, in June 1943. Mother is cleaning fish in a basin on top of the well cover. The box contains iron nails collected by the family, and other iron supplies found in the ruins of other burned houses, to be used in reconstruction.

PHOTO Aukusti Tuhka

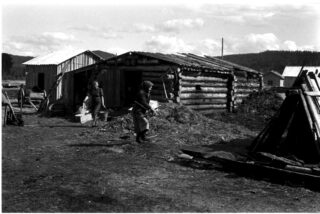

Kalle Takalo with his family on the steps of his new house in 1943. When the Winter War broke out in November 1939, in accordance with scorched-earth policy, the Finnish retreating troops destroyed the buildings of Paanajärvi and other border villages, after the inhabitants had been evacuated. Paanajärvi was ceded to the Soviet Union in the peace treaty that ended the Winter War, but the Finns reconquered the area in the Continuation War and annexed it to Finland at the end of 1941. Like the Takalos, many families returned to their home area during the Continuation War, to rebuild their homes. After the war ended in 1944, Finland again had to cede Paanajärvi to the Soviets, and the village inhabitants were resettled elsewhere in Kuusamo and Finland.

PHOTO Aukusti Tuhka

In mid 1990s, volunteers organized by the Paanajärvi-Tavajärvi Society restored the Paanajärvi graveyard, which had been used since 1934. With support from the Ministry of Education, the graveyard gate, fence and monument were completed in 1999. The graveyard is located by River Oulankajoki, near the River Kuusinkijoki fork and the border between Finland and Russia.

PHOTO Kari Kantola

A boy from Porovaara and his fine catch in July 1945. In post-war Finland there was a shortage of everything, and even the help of a little boy in getting food was important to the family. Porovaara is located by the former Paanajärvi road in Paljakka, Vuotunki.

PHOTO Aukusti Tuhka

Rajala was one of the best-known houses in Paanajärvi, and a place where also travellers stayed. In 1892, Akseli Gallen-Kallela and his family stayed at Rajala, from where it was easy to go to paint at the Mäntykoski rapid. The Uunikivi cliff and shore, from where the villagers quarried stones for building, were also located by the lake, quite close to Rajala.

PHOTO I. K. Inha, Ethnographic Picture Collection, Finnish Heritage Agency

Uunikiviranta shore, Lake Paanajärvi, pictured east from Ristiniemi. The high fell in the background is Uravaara, with Heikkala (Pauna) farm below. To the right are the fields and farmhouse of Rajala. The spit of land is called Paanan niemi (Paana point).

PHOTO I. K. Inha, Ethnographic Picture Collection, Finnish Heritage Agency

Kivakkakoski rapid, River Oulankajoki, in 1894. From here the river flows between Vartiolampi village and Kivakkatunturi fell down to the next large basin, Lake Pääjärvi.

PHOTO I. K. Inha, Historical Picture Collection, Finnish Heritage Agency

Young bear hunter Aadolf Pesonen, 16. Like his younger brother Antti, Aadolf posed for Akseli Gallen-Kallela in 1892.

PHOTO Akseli Gallen-Kallela Photograph Collection

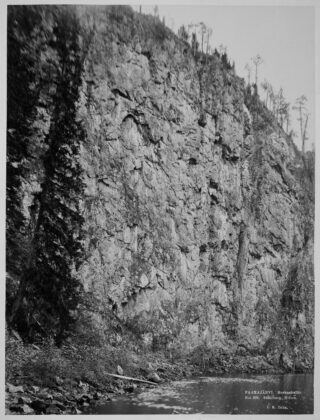

Ruskeakallio cliff, Lake Paanajärvi, photographed by Esko Suomalainen in 1935. Ruskeakallio cliff rises from the lake surface to a height of 60 metres. At Ruskeakallio cliff there are depressions in the lake floor that reach a depth of 128 metres.

Behind Ruskeakallio cliff, Mäntytunturi fell rises to an elevation of approximately 550 metres, so the differences in altitude here are great.

PHOTO Esko Suomalainen

Ruskeakallio cliff rises from the lake surface to a height of 60 metres. At Ruskeakallio cliff there are depressions in the lake floor that reach a depth of 128 metres. Behind Ruskeakallio cliff, Mäntytunturi fell rises to an elevation of approximately 550 metres, so the differences in altitude here are great.

PHOTO I. K. Inha, Historical Picture Collection, Finnish Heritage Agency

In the 1930s, Iivari Yltiö, the farmer from Päätalo, used his motorboat to take travellers and, at some point, also mail on Lake Paanajärvi. The metal boat could carry some 20 passengers.

PHOTO Väinö Manninen

A mother with her children in Paanajärvi in 1917.

PHOTO Samuli Paulaharju, Ethnographic Picture Collection, Finnish Heritage Agency

Three girls skiing on the ice of Lake Paanajärvi in the 1930s.

PHOTO Uuno Peltoniemi, Ethnographic Picture Collection, Finnish Heritage Agency

A farmer with a birch bark horn, Paanajärvi, 1934.

PHOTO Kuopio Cultural History Museum

People from Kuusamo parish village on a day-trip to Paanajärvi in the 1920s.

PHOTO Kinnunen Photo Archive

PHOTO Anneli Meriläinen, in her book Paanajärvi, 1993